Editor’s Note: This article is a first person AAR of the final flight of Dumptruck-12, which crashed in Darwin, Australia on Sunday, Aug. 27, 2023. The Connecting File remembers and honors the sacrifice of Cpl. Spencer R. Collart, Capt. Eleanor V. LeBeau and Maj. Tobin J. Lewis.

Prep for combat is everything; everything is prep for combat.

These are the words every prospective 0302 hears in one of their first moments at the Infantry Officer Course. Many of us take this to heart immediately, but it isn’t until you experience it for real, that you truly metabolize its meaning.

For myself, and many of my Marines, this phrase and vital habit, became reality on 27 August 2023.

While on approach to the objective, an MV-22, callsign Dumptruck 12, crashed into the Australian jungle with 19 Marines seated in the back of the aircraft. The mishap resulted in the death of three Marine aircrew, life threatening injuries to one crew chief, and serious injuries to six other infantrymen and one Navy corpsman.

Upon impact, the immediate reaction of the passengers in the back was to egress through the only tenable hatch, the rear ramp of the aircraft. Within approximately 60 seconds of impact, the remains of the aircraft were completely engulfed in flames on all sides. Approximately two minutes after impact, all Marines had exited from the aircraft and rescued the one surviving member of the aircrew.

The situation that ensued over the next five hours, until all survivors were extracted, produced many lessons learned that should be considered for future leaders conducting assault support operations.

The Situation

In the last weeks of a routine deployment in support of Marine Rotational Force Darwin (MRF-D) 23.3, 110 Marines of Lima Company, callsign Lonestar, of 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, stepped off on EXERCISE PREDATORS RUN in Australia’s Northern Territory in the vicinity of Melville Island.

Pred Run is an annual three week bi-lateral exercise focused on expeditionary advanced base operations in the littorals around Darwin. The exercise is usually a mix of both live-fire and force-on-force, with this year’s event consisting of units from 1st Brigade, Royal Australian Army and MRF-D 23.3.

For this exercise, Lima was tasked to seize two airfields on Melville Island through an air assault, which would then be exploited by the 5th Royal Australian Regiment (5 RAR) in the form of a small boat beach landing followed by a movement to contact. These actions would take place in a semi-permissive environment. Ultimately, the purpose of the exercise was to increase interoperability between our forces and to build upon an already sound, strong, and tested relationship.

Due to resource shortfalls, Lima developed a scheme of maneuver to take down the airfields sequentially rather than simultaneously. The force was then split; as the Company Executive Officer, I would lead 38 Marines to seize the southern and smaller airfield named objective “Cheetah” first, and the remaining 72 Marines, led by the Company Commander, would seize the northern, and larger objective, "Alpaca,” second. The two airfields were to be treated as independent objective areas. The CO and I would be assault force commanders (AFC) for our respective objective areas, each of us owning our own battle space.

On an otherwise quiet Sunday morning, my force destined to OBJ Cheetah boarded two MV-22s, with 19 Marines per aircraft. After completing a 40 nautical mile flight and a tactical approach as a section of aircraft, the lead aircraft safely landed in the objective area.

But with little warning to the Marines in the back of Dumptruck 12, the dash 2 aircraft crashed into the jungle approximately 2 kilometers short of the LZ. Immediately after impacting the deck, the aircraft was almost instantly entirely engulfed in flames, filled with dirt and debris, and spraying fuel and fluids. Other than the few who were warned just seconds prior of the expected crash via ICS, Marines who retained consciousness were in a state of shock and disorientation.

A mixed section of AH-1Z and UH-1Y who were escorting the assault force remained overhead of the crash site and quickly assumed the role of On Scene Commander (OSC).

After coming to a stop and recognizing that I was alive, my mind turned to getting everyone out. Due to the intense fire, smoke, and debris filling the cabin I reverted to thinking of alternate escape routes considering the rear ramp may not be tenable. I had an explosive escape window over my left shoulder, and the forward right hand crew door available, but both were engulfed in flames. The only light piercing through the smoke came from the rear of the aircraft and this soon became the primary exit.

Within the cabin, it was a relatively calm situation, mostly attributed to the pure shock of what had just happened and several unconscious Marines. After recognizing that nobody was really moving, I yelled to the Marines “leave everything and get out the back.” As I unstrapped and untangled myself from the ICS cord and pushed gear to the side, I noticed my young Radio Operator (RO), who was seated by the cockpit, was slumped forward and unconscious. I checked the Marines to my right and front to make sure they were alert enough to get moving and then turned back towards my RO. After unharnessing him, I began to push him towards the rear exit, checking under seats as I went to ensure no one remained trapped. As I made it to the ramp, I handed off my RO to another Marine and stood at the ramp making one last visual inspection of the cabin for survivors. As I turned and began to step off, I was met by another chaotic scene.

Still standing at the rear of the aircraft from which the fire was rapidly spreading, I witnessed the rear member of the aircrew who was pinned underneath the fuselage of the plane and severely injured, being cut free and buddy dragged to safety by my Marines who had come back to his rescue.

Looking rearward into the jungle, smoke was billowing and flames were spreading. The debris field was large and spread in a linear fashion from how we had entered the treeline. Marines were immediately yelling for others in their fireteam and moving rearward in a disorganized fashion, just trying to get away from the aircraft with the thought that it might explode.

Within a few moments, my FiST leader and the platoon commander asked for tasking. I directed them to gain accountability and to once again confirm we had no Marine left inside the aircraft. On initial report, 20 Marines were reported accounted for, everyone from Lima plus one member of the aircrew. However, that left the aircrew, of which there were 3 more aboard, the 3 being our pilots and the forward crew chief.

With this accountability, I directed the FiST leader to take a buddy and conduct a 360 degree sweep of the immediate surrounding area, assuming the missing three may have escaped forward of the aircraft.

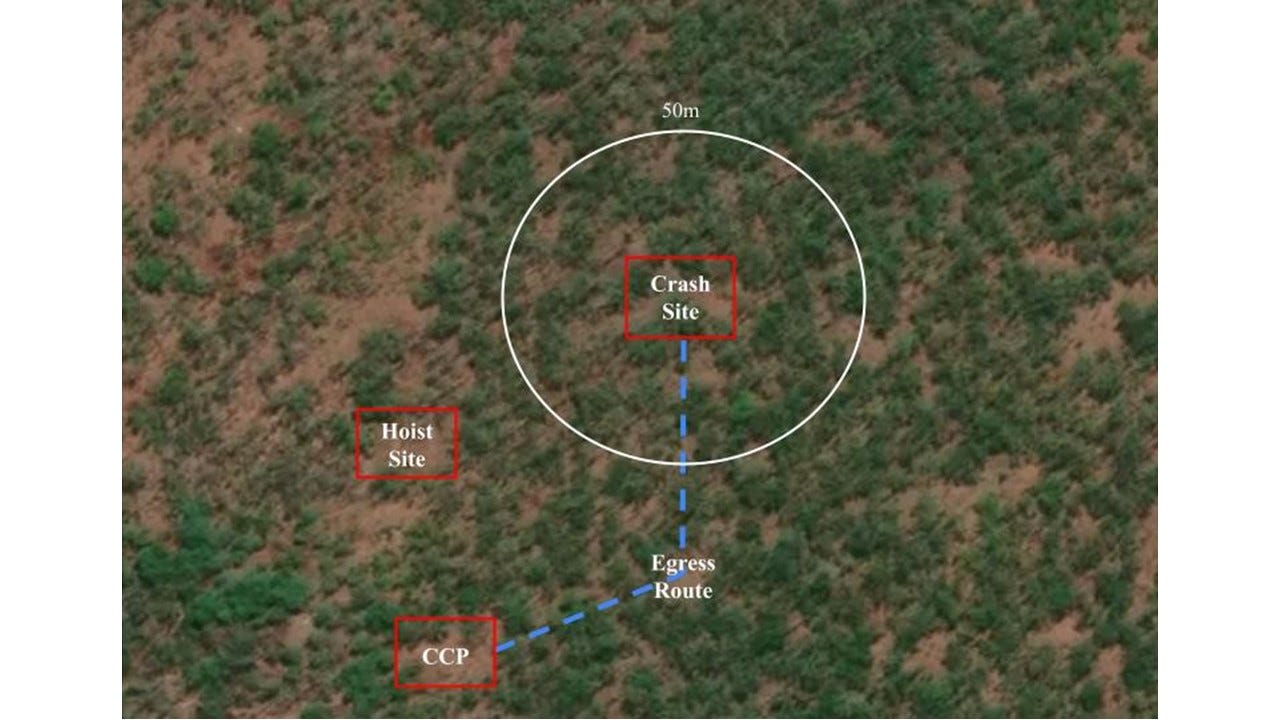

Next, I directed two NCO’s and the platoon commander to push everyone 100m to our rear and establish a CCP, conduct initial triage, and generate ZMIST reports for any urgent and priority casualties.

I then placed myself halfway between the aircraft and the CCP. After several minutes I was able to establish communication with the overhead helicopters and pass a SITREP, accountability, and my intent: to hold everyone in place, stabilize casualties, and execute a search for survivors. Initial triage reports from the NCO’s at our CCP reported 1 urgent and 2 priority casualties with multiple possible routine/additional priority casualties. I also requested life flight assets with hoist capability, and for a direction and distance to the original LZ to begin to build my SA.

45 minutes after the crash, a team of about a dozen Australian soldiers made their way to us on foot to assist with search efforts. A half hour later, the first of several civilian MEDEVAC aircraft arrived on scene, hoisting in medical personnel. By three hours after the crash, Australian ground transportation arrived, and began shuttling Marines to the original LZ for extraction back to Darwin and medical treatment.

In the end, five hours after the crash, myself, the FiST leader and platoon commander were evacuated and the scene was handed over to squadron investigators and Australian government officials.

Planning: Capabilities and Communication Matter

Commonly, and according to the Assault Support Tactical Standard Operating Procedure (ASTACSOP) guidelines, it is not suggested to have multiple key leaders or key capabilities on one aircraft due to potential asset attrition and loss of critical capabilities. Ultimately, in this evolution, due to exercise design requirements, there were multiple key leaders and capabilities aboard the mishap aircraft. This included myself, the XO (Assault Force Commander and approval authority of all fires), Fire Support Team Leader (coordinator of all fires), Rifle Platoon Commander (security force leader), machine gun section leader, and mortar section leader. The “planned” number of Marines to be inserted was 38. However, the “Go” and “minimum boots” number of Marines was 19, consisting of these key leaders and BLOS communication equipment. In other words, without all these particular 19 Marines inserted in one wave at the same time, the assault force would not meet the criteria required to insert any Marines at all, triggering contingencies and delaying the larger scale exercise objectives for our international partners.

When conducting air assault operations, it is critical to not only consider the spread of key leaders, but critical capabilities. Planners must have a deep understanding of the verbiage used in assault support planning. It is very important to understand the difference in nomenclature with regards to go criteria (planned vs go vs minimum boots on deck). In planning, the main thing that matters to the ACE is the number of people and things that are getting moved, and furthermore, what is the minimum number of people that can accomplish the mission (otherwise known as the “go” number).

When utilizing the GCE ground coordination checklist in an air assault planning session, the number of people (go and minimum boots on deck) is what GCE planners will be pressed to deliver. However, as an assault force, we must go further and deliberately plan for not only people, but also what capabilities we are spread-loading and where they are located in the list of priority serials.

Plan for what makes sense. Spreading key leaders for the sake of spreading key leaders might cause more friction by not having critical capabilities together (JTAC and AFC). Consider who needs to be paired together in flight and who must be inserted together for mission accomplishment, and who does not need to be together for the transit.

Upon the dash 1 aircraft making a safe landing, the Marines were kept onboard and not allowed to leave their seats. While frustrating to those who had just witnessed the second aircraft crash, the decision to keep them onboard versus allowing them to try and locate the crash site and assist was the right call. Due to the complex terrain and distance, if they were allowed off, due to their lack of communication equipment, key leaders, and lack of situational awareness, adding another 19 Marines into the equation would have been more of a liability than a help. In this situation, if dash 1 had gone down, due to the lack of communication assets and key leaders aboard, the recovery phase arguably would have proved to be a far greater challenge. Though I have advocated for prioritizing the load plan based around the mission itself, one must understand that you are also putting yourself at risk in the case of contingencies.

Communicating and Sharing Your Decision

During the planning process, version control of the final air manifest and Assault Support Serial Assignment Table (ASSAT) was troublesome, with multiple units having different versions of the same document. Ensure all parties have the same versions of documents that you, as the assault force, are working with and that you stick with the naming conventions detailed in WTI Planning SOPs. The final version produced by the assault force is the version that matters. Minimize version control errors by finalizing and distributing the manifest and ASSAT as close to the mission as practical.

For billet holders, it is recommended that squad leaders and up, in addition to stick leaders, carry a printed-out copy of the entire air manifest and ASSAT on their person for redundancy in the event of any last-minute unavoidable changes. Ensure they are aware of exactly who is in their stick, and that they have positive accountability of the numbers prior to boarding and takeoff. Write on each Marine’s hand, in permanent marker, their serial number. This all proved to be essential, and potentially life saving, following the mishap.

Having universally accurate serials saves you critical time. “Serials 3000 and 3010 accounted for. Serial 3005, Line 3, Urgent casualty,” is much quicker than now needing to pull and pass ZAP numbers. Incorrect reports will further complicate matters and snarl recovery efforts.

Coordinate directly with ACE players to facilitate their planning, however, handing the aircrew a manifest and ASSAT as close to launch as is acceptable will reduce version control errors and ensure that the aircraft commander has proper accountability. Confirm with the crew chief and aircrew prior to loading that all leaders have the same document and information. The same goes for other key leaders and planners throughout the MAGTF who are partaking in the operation.

Key Take Aways:

Having a common language among MAGTF planners is vital. Specific words mean specific things to everyone.

Load the aircraft per mission requirements - not doctrinal recommendations.

Version control of the ASSAT is a must. Distribute it at the last possible moment.

Rehearse: Nothing is Too Small or Extreme.

Like everything we do, rehearsals are critical to successful execution. It is critical as a leader to continuously rehearse the little things in your training time, knowing that every minute you have for rehearsals in the future is precious and finite. Know your Marines and your unit, and focus their preparatory efforts IAW a sound and deliberately prioritized rehearsal plan.

Oftentimes due to geographic separation, or scheduling obstacles, infantry Marines do not get repetitions of rehearsing on assault support aircraft prior to executing heliborne operations. However, squadrons are often more than willing to accommodate static on and off drills with their aircraft on their flight lines and actually encourage these drills as frequently as possible.

In typical safety briefs given by aircraft crew chiefs while standing close to a spinning aircraft, Marines are briefed that in the event of an emergency to look to the crew chief for directions on egress. In our situation, both crew chiefs were non-ambulatory and unable to assist in egress due to injuries sustained during the impact. Without small unit leaders who were able to take control and provide direction, more lives would potentially have been lost. We as infantrymen take rehearsals seriously for actions in the objective area, why would we not do the same for arguably the most inherently dangerous part of the mission: the take off and landing of an aircraft?

Lima had conducted two flights on MV-22B’s within the preceding year and static on/off drills with full kit and main packs one other time in the same period. The value of maximizing this minimal experience cannot be overstated. On/off drills, while seemingly simple and often overlooked, provided every Marine in the company the opportunity to gain basic familiarity with the MV-22 prior to the mishap. Location of emergency windows, the use of the safety harness, the operation of all egress points, and location of all safety equipment were known to leadership, and likely all Marines, by memory prior to this training event. Upon initial impact in the crash, I could not see the Marine seated 5 ft across from me, nor could I see out of the rear ramp of the aircraft. Heavy flames, thick smoke, spraying fluid, dirt, dust, gear, and aircraft wreckage made visibility extremely poor. Additionally, the heat from the fire was overwhelming to say the least. Anything that was not strapped down became a projectile flying from the rear to front of the aircraft. I have little doubt that being familiar with the aircraft was a critical factor in the ability for all Marines to self-extricate or extract fellow Marines who were unconscious in a low visibility and chaotic environment.

Key Take Aways:

Think critically about your prioritization of rehearsals, select them deliberately, and rehearse them ruthlessly.

Maximize all available training time aboard vehicles or aircraft in order to build familiarity in the event of emergency.

Don’t solely rely on crew chiefs or operators to come to your rescue in case of a mishap, they are oftentimes more vulnerable than those strapped in.

Prepare for the Worst: Anything is possible

The Importance of a Gear SOP

Gear common to all guidance often varies by unit and by echelon of command. When conducting an air assault, there are arguably a few extra items that should be considered gear common to all for each Marine for use in heliborne operations and in the event of a mishap. Additionally, standardized gear placement, or location, as well as type of gear, is also critical.

In the chaos of the crash, the Corpsman’s primary medical bag was unrecoverable, resulting in reliance on Individual First Aid Kit (IFAK) supplies from the rest of the Marines. However, many Marines stored their IFAK on a sub-belt that was kept around the main packs during the flight in order to physically fit in their seat with the harness properly worn. Additionally, many Marines did not have a tourniquet or knife on their person. With no time to grab main packs, only about half of the Marines egressed the aircraft with an IFAK, severely limiting the corpsman’s ability to triage and treat patients.

In the aftermath and due to a leadership failure in ensuring proper PCC’s and enforcing of the commanders field guidance, some Marines were identified as having gone on the mission with personalized kill patches for their body armor, name tapes that were nicknames, or did not have a common access card (CAC) in their cammies. These unfortunate details led to self-induced friction in identifying casualties, as well as generating accurate and timely reports required for medical assistance. Fortunately, this was resolved with an accurate by name manifest retained by myself and other key leaders, and helped us to avoid delays that could have resulted in the deterioration of patient status.

Key Take Aways:

Position the IFAK in a standardized location on the plate carrier, or belt, and in a manner that allows for proper harnessing in either a vehicle or aircraft.

Standardize unit patches and placement of ZAP/kill cards.

The Individual Issue Facility issued strap cutter is a must for all flight or vehicle operations. If not on hand, every Marine must at least carry a knife to be able to cut away themselves or a battle buddy.

Leaders supervise PCCs.

Prioritize and Triage: Accountability, Casualties, Communication

When facing the worst possible scenario, prioritizing immediate actions may make the difference between life and death. This goes double for a Mass Casualty situation. There are a number of important questions and tasks to attend to amidst the backdrop of a chaotic environment: Is everyone alive? Who is injured? Is anyone trapped? How are we going to get out of here? Does everyone have their weapon? What assets do we have available to assist us? How far do we need to move to stay safe?

This situation being a training environment in a friendly nation, the enemy was classified as fire, hazardous materials, terrain and weather. However, the principle does not change: Keeping an “enemy” focused mindset and/or a “what is going to kill us first" mindset along with identifying who is the most at risk of death needs to be at the forefront of a leader's mind.

With this in mind, my priorities of work after egressing the aircraft as the Ground Force Commander, and the most senior leader alive after the crash were: accountability, casualties, and communication.

Accountability

This drives everything. I quickly found the FiST leader and platoon commander. I ordered the FiST leader to take a buddy and conduct a 360 sweep of the surrounding area to locate the other members of the aircrew, who I suspected of potentially egressing forward of the crash, and the platoon commander to gain accountability of the rest of the force. We need to know if we have all of our people and immediately turn to locating those unaccounted for.

If they are trapped, who is going to extract them and how? If they are lost, who is going to locate them? If they are unaccounted for and there is a suspicion of their death, who has the authority to call off a search in the interest of preventing further casualties? Even in an aviation related or vehicle mishap, a Lost Marine Plan is necessary. It can be as simple as: “In the event of a mishap, the muster point will be at the 6 O’clock position of the crash site at a distance of 100m. If you are not located at that point within 3 minutes, a search party will begin conducting 0/5/25’s until you are located. If you are not located at this point, we will continue expanding our search pattern until an appropriate authority directs the search to be terminated.”

While still positioned at the rear of the aircraft in the event that we did not have everyone accounted for, I was prepared to go back in to find that Marine. However very quickly, my key leaders reported they physically have seen every Marine under their charge verifying each name on a hard copy manifest.

Casualties

Prefacing this, a MASSCAS that occurs in a training environment is inherently going to have a different order of priorities versus one occurring in a combat environment with a live enemy threat. The “threat” in this situation was first the ongoing and spreading fire, and second, the likelihood of a subsequent explosion.

After confirming accountability, an initial triage of all Marines is critical. I tasked two NCO’s to establish a CCP, 100m to our rear, consolidate the force, identify our casualties, separate them by precedence and generate ZMIST reports for each one. All Marines should be capable of these tasks.

Self-aid, buddy aid, Corpsman aid. Even though a Marine may appear and report to be uninjured, keep in mind they might be in shock and have adrenaline masking potentially severe injuries. Concurrently, a casualty collection point needs to be clearly established at a safe distance from the threat, in this case fire and potential secondary explosions, in order to allow the Corpsman to do his job.

If casualties are deemed too unstable to move due to the condition of their injuries, a decision must be made to either move them to a safer location, or leave them in place in hopes of not furthering their injuries. From a medical perspective, with the high suspicion of internal injuries that we could not see, I elected to leave our most severely injured in a less than ideal location, at the gain of not causing further harm.

Critical Tasks:

In a mass casualty situation, remaining calm is key.

Appoint a leader to be in charge of accountability at the casualty collection point.

Separate casualties by precedence.

Consolidate the available medical supplies in a central location and provide support to the Corpsman as required.

Able bodied Marines need to treat as much as they can and leave the heavy lifting to the Corpsman.

Prepare Z-MIST reports for each casualty and consolidate to the leadership to send to HHQ.

Prevent unnecessary further injury at all costs especially when the future is unknown.

Communication

This must be understood in two ways - communication internally to your unit and externally to supporting agencies.

Internal:

It begins internally. Just like in any IA Drill, you react to the threat and issue your order before calling higher.

Leaders talk to leaders. Bring in your key leaders and give specific directions. When able, talk to the Marines and inform them of the status of recovery assets.

Remember the human dimension and maintain clear and concise communication. Marines are in shock and adrenaline is likely running extremely high. Marines need to be kept calm, given specific orders, and informed of the situation that is unfolding.

Ensure regular checks are being conducted on casualties to determine if any of the injured personnel are deteriorating, hence changing your requirements for assistance.

External:

Up and out communication, likely via radio, is crucial. In a crisis, fighting for comm is your lifeline. Know the appropriate frequencies and cycle through them until you reach someone. Bottom line: Run through the PACE plan until you reach someone and fight for comm.

Understand that aircraft radios work predominantly on a line-of-sight system. Being on the ground and in a wooded area will likely have challenges due to a potential loss of line of sight with the aircraft, however, this can be mitigated by moving your position, the angle of antennas, and trying multiple frequencies.

If the situation permits, rolling to PT to eliminate possible crypto discrepancies may be a good option. The emergency frequencies of 121.50 (VHF) and 243.0 (UHF) are also options which most if not all aircraft and air traffic control agencies will monitor.

When you reach an outside agency, clear concise communication is critical. Have your report prepared before you key the mic.

As the ground force, you will be working hand in hand with the airborne on scene commander (OSC) to coordinate search and rescue, TRAP, and medical evacuation assets on the scene. Tell them what you need and let them work for you.

Gather as much up and out situational awareness as possible, digest it, and make an informed decision to allow the OSC to pull the correct amount and type of resources to your aide.

Key Takeaways:

Have established IA drills and rehearse them.

Clear roles and responsibilities are a must, as well as the ability to perform the duties of others.

Be ready to prioritize your decisions, your actions, and your reports.

Save Lives: This is the new mission

Approximately 80% of the Marines in Lima Company were certified in basic combat lifesaving (CLS) prior to this mishap. The Marines were prepared and their training kicked in immediately upon impact. Lives were saved. However, in a mass casualty scenario such as this one, with only one Corpsman available, Marines are required to assist to a greater degree than their training may support. If all Marines had been trained in more than basic TCCC, this would have allowed the corpsman to supervise treatment and focus exclusively on those in most urgent need of treatment. Additionally, consider the following:

Require the practical application of TCCC skills in the training environment as frequently as possible. Utilize dynamic scenarios that go beyond the commonly trained to “gunshot wound” and require more skill than a tourniquet application. Forcing decision making and critical thinking is a massive benefit to both them, and the unit.

Develop and rehearse your unit’s mass casualty SOP and test it against a multitude of scenarios.

Aim to have at least one Marine per rifle squad trained in advanced CLS to supplement the Corpsman when needed.

Invest in CLS bags so every rifle squad has access to them and has the capability to carry more advanced medical equipment

Have conversations with the Marines about how adrenaline can suppress serious injuries. After a traumatic experience, leaders must assume everyone is a casualty until cleared by trained medical personnel. Failure to do so will lead to more injuries and potentially death that could be avoidable.

This will not only ensure Marines are able to save each other’s lives, but it will also provide a force multiplier when there might not be enough Corpsmen on scene, such as in a mass casualty situation.

Be a Leader: Our Nation is Counting on You

Prior to gaining communications with the overhead Escort Flight Lead, who was now the OSC, I had little to no situational awareness of anything outside of my immediate surrounding area. In order to quickly orient myself to the situation and look for solutions, I pulled and plotted a position from a wrist-worn Global Positioning System (GPS). This initial position placed us just 300 meters away from the intended LZ where further assistance was located. Perfect... I’ll send a team to make contact and pull ground recovery assets to us and expedite the extraction of our most severely injured.

However, after gaining communications with the OSC several minutes later and upon cross checking our position, the OSC informed me that in fact we were almost 2000 meters away from our objective through dense and rugged terrain. Furthermore, the OSC was able to provide clear and reassuring communication throughout on recommended courses of actions and options available based on our deteriorating situation. Rather than feeling alone and pressured to make a decision immediately, I should have leveraged the EFL earlier. The EFL’s advantageous position in the overhead would have been helpful in providing options and in helping me create a game plan sooner. This would have saved valuable time.

Remember to ask available assets, who have greater situational awareness than yourself, for their recommendations, options available, and solutions prior to making decisions - if time allows. Rushing to failure is a potential consequence if you don’t attempt to flush out your estimate of the situation. As the leader on the deck, you will be the main effort, again, let others work for you as the supporting efforts. Making decisions for the sake of making decisions is not what we get paid to do. We have to use judgement and leverage the best information available. Sometimes that requires taking a deep breath and building a complete sight picture by talking to an outside agency who can help.

The Aftermath:

As a unit, Lima Company had just experienced harsh and unexpected trauma. Marines did not want to get back on another aircraft. But letting this event become a limiting factor within the formation was not going to be an option... our only option was to “get back out on patrol.”

With redeployment quickly approaching, leaders fought to get back on the aircraft as soon as possible. The squadron fought to get back airborne as quickly as possible. Within two weeks of the mishap, Lima company returned to the flightline aboard Royal Australian Air Force Base Darwin and conducted on and off drills from the MV-22.

With rotors turning, Marines did what they do best. Injured Marines watched from the sidelines, and some hobbled back onboard to the seat they occupied during the crash. Emotions ran high, but this was not only an important step in the healing process; it was one that would prove critical for future training involving assault support operations.

Thoughts of losing Marines during routine training, or in a friendly partner nation, are often not at the forefront of our minds. We certainly recognize the risks we take and mitigate, but our ROCs and contingency planning rarely include discussions of actual death. 27 August was a routine bilateral exercise. As the adrenaline of the day began to wear off, pain began to set in, and the reality of what just occurred was staring the Marines in the face.

But we soon realized the two units involved were forged in a bond that was unlike any before. While having never been to combat myself, experiencing loss in an unexpected situation was tough on me and my Marines. A routine training exercise turned deadly; and symbolized the beginning of a long fight for many. The days, weeks, and months following presented challenges that were novel and difficult. Many of the infantrymen who were in the back of Dumptruck 12 are reminded daily of those lost whenever they glance at, or are physically reminded of the injuries they sustained. And of course, upon returning home, Marines began to move on in the weeks and months following the deployment. As the one-year anniversary came and went, emotions were palpably higher in the formation.

The emotions you can feel after leading your Marines through a traumatic event have the potential to be long lasting. While those we lost that day were not part of our company, it certainly felt like our ranks were diminished on August 27. Survivors' guilt is something a leader needs to be prepared to confront. Did I make the right call? Was there something I could have done better? Was I brave enough? Did I further injure any Marines? These questions can remain with you long afterwards. Major Geoff Ball put it well in his article on leading through casualties:

“As a commander this is when you feel the loneliness the most. I will be forever grateful to the NCOs who pulled me aside and said: ‘Sir, we’re really glad you were there with us.’ These words kept me afloat amidst severe moments of doubt, shame, and guilt.”

To this day, Marines from Lima 3/1, VMM-363, HMLA-367, and the families of our fallen continue to support each other. In the days following the mishap, our three units gathered together, regardless of rank, to connect and process. Later that same week, we bore witness to the flightline memorial ceremony and dignified transfers. We all heavily relied on this newfound camaraderie to help us get through these significant early milestones.

In the following year, myself, and several other Marines from Lima, wrote letters to the Gold Star families. To my surprise, they all wrote back. Since then I have had the opportunity to meet them all personally and we communicate frequently. Just over a year after the mishap, I was honored to run the 249th Marine Corps Marathon alongside many of these family members in memory of their fallen loved ones.

Keep your Marines close. Bring their families into your lives. Don’t fear them. By keeping the names alive, together, you all will see your way through.

I’ll close with this: when you take the oath of office, you are telling your country that they can turn to you when everything goes to hell. You are saying that you are ready to accept the responsibility of leading young Americans through the worst day of their lives. The mothers and fathers of our Marines expect this from us when they entrust us with their sons and daughters. Ensure you are ready to meet your moment.

Captain Joshua Watson is an infantry officer and currently a student naval aviator in Pensacola, FL. He can be reached at joshua.watson2@usmc.mil. He writes this in memory and in honor of the heroism of Cpl. Spencer R. Collart, Capt. Eleanor V. LeBeau and Maj. Tobin J. Lewis. Without their complete dedication to duty, he would not be writing this today. Semper Fidelis.

There's a ton of great points in this, but the "get them back on the horse" position may be the most important piece. I hope people at EWTG's TRAP Course are reading this and handing out copies to the Lts and SNCOs going through that course.

We are very grateful, Josh, for you, the amazing person you are and that you were in that plane. We consider that a divine appointment. Thank you for making the time and effort to delineate what took place in the back and especially the lessons learned. Although Toby died trying to save everyone, you heroically completed that miraculous feat. Now he has passed the baton to you & is cheering you on from above as you become an aviator. We’re cheering for you, too.

Norm & Kathy Lewis