Redefining LAR Operations: Autonomous Systems and a Leaner Table of Equipment

LtCol John Dick

At 0400, a 3d Light Armored Reconnaissance’s (LAR) Company sat staged in defilade behind a ridgeline overlooking a key choke point on Luzon Island. The platoon commander had pushed scouts forward, but they were down to 40% ammunition after a 36-hour movement to contact. Enemy drones loitered overhead, and the only known resupply corridor was under intermittent artillery fire. A traditional combat resupply convoy consisting of Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTV) and Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacement (MTVR) 7-tons would have been highly visible in spectrum and attacked to prevent needed supplies getting to the Marines. Instead, two Expeditionary Modular Autonomous Vehicles (EMAV) and one Multiple Mission Silent Partner (MMSP) and seven Tactical Resupply Unmanned Aircraft System (TRUAS) TRV-150C, quad-rotor drone, moved autonomously through ravines and overgrown jungle. Within 90 minutes, both platforms arrived at the preloaded grid reference point. The Marines offloaded CASEVAC kits, ammunition, and radio batteries, all without exposing a single crewman or emitting a detectable signal. The convoy never rolled. The fight never paused. The Company stayed in the fight.

This is a glimpse of what LAR operations could become if they deliberately reduce the Table of Equipment (T/E) and integrate unmanned systems designed to meet emerging threats and align with the future trajectory of Marine Corps modernization.

This article proposes a deliberate reduction of up to 50 percent of the LAR battalion’s manned tactical vehicle fleet—specifically, the divestment of (15) MTVRs, (2) MTVR Armadillos, (2) LVSRs, (1) Flat Track Refueler (FTR), and (4) HMMWVs. Accompanying these reductions are efforts to rationalize duplicate power systems and consolidate sustainment toolsets. This force design refinement supports the Commandant’s directive to eliminate over-structured support formations while preserving—if not enhancing—operational effectiveness. By shedding redundant platforms and reinvesting that space, weight, and power margin into emerging autonomous technologies, the battalion gains the ability to operate with greater endurance, reduced sustainment burden, and drastically lower signature—an operational necessity for stand-in forces operating inside the weapons engagement zone (WEZ) of a peer adversary.

Unmanned systems are no longer experimental—they are scalable, field-ready, and aligned with the doctrinal shift toward contested logistics and distributed operations. TRUAS (e.g., the USMC’s TRV-150C prototype) can deliver up to 150 lbs of supplies over 9–25 km, making them ideal for urgent Class V, III, or IX resupply to dispersed units. Expeditionary Modular Autonomous Vehicle (EMAV)-style Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs), weighing approximately 7,000 lbs, offer autonomous lift capacities of 1,000–7,000 lbs and can traverse complex terrain for extended durations with electric or hybrid-electric powertrains. These systems, fielded in combination, enable decentralized and risk-tolerant sustainment in environments where traditional convoys would be vulnerable to detection, interdiction, or denial.

Current Logistics Formation Types

The Battalion Main and Forward consists of five to seven vehicles, while the Combat Logistics Trains (CLT) can field up to 30 vehicles, supporting company and battalion operations. Examples:

Battalion Main Command Post: Consists of five to seven vehicles (including JLTVs, MTVRs, and trailers), and four to eight Light Armed Vehicles, primarily for command and control and higher-level coordination.

CLT: Usually consist of 24–30 vehicles, often including:

Six to eight MTVRs (7-ton trucks) each capable of carrying 15,000 lbs

Three to four Logistics Vehicle System Replacement (LVSR) for heavier loads

Multiple JLTVs / High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWV), Trailers, and Wreckers

This logistical tail supports a forward-deployed LAR Battalion by delivering fuel, ammunition, water, and Class IX (repair parts), while also coordinating with CASEVAC and maintenance operations. However, this structure is manpower-intensive, requires constant Preventive Maintenance Checks and Services (PMCS) cycles, and poses a significant target to enemy Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) and fires in peer-contested environments.

TO/E Optimization: Fewer Trucks, More Capability

A conservative capability estimate suggests that replacing one MTVR (15,000 lbs capacity) would require approximately:

Ten TRUAS sorties for distributed emergency resupply (1,500 lbs cumulative).

Four to five EMAVs operating in relay or swarm configurations for bulk transport missions.

Extrapolated to the company or battalion level, a Combat Logistics Train (CLT) that previously deployed with six MTVRs could replace that capacity with 10–15 EMAVs and 40–50 TRUAS sorties per day—effectively sustaining operations without exposing Marines, generating engine signatures, or requiring extensive route clearance and security.

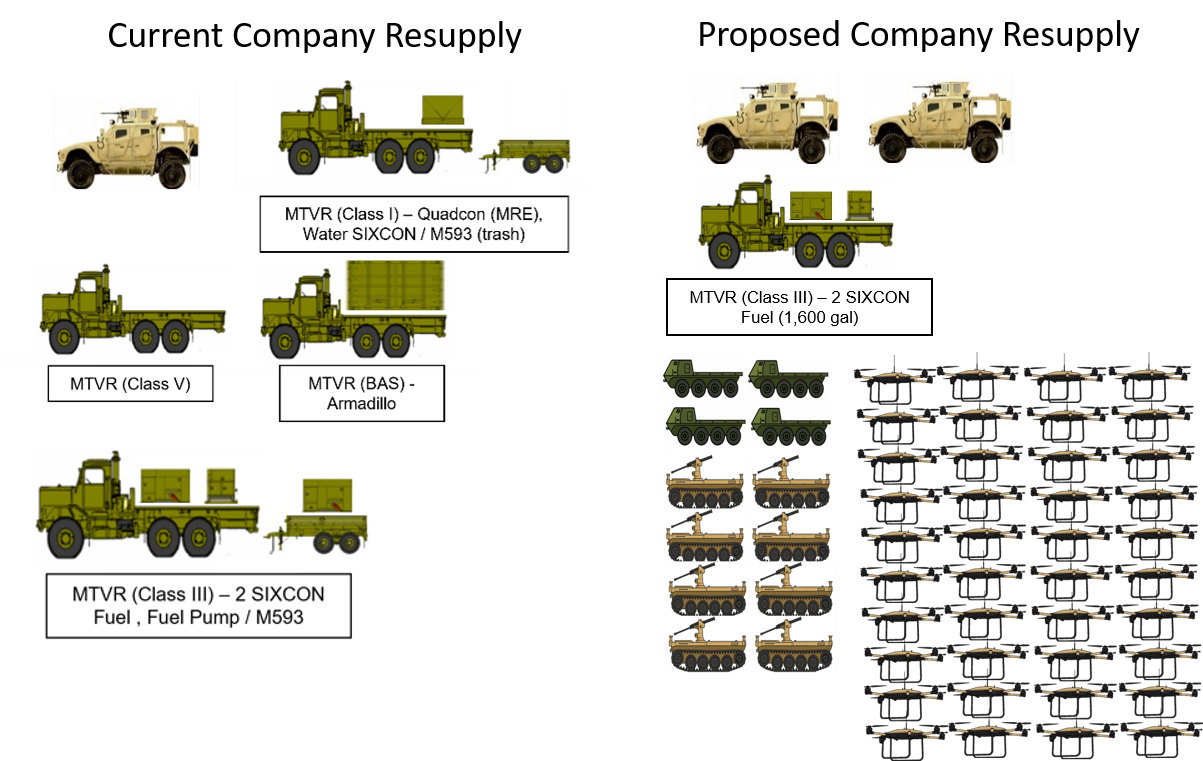

The graphic below illustrates replacing the MTVR as the backbone of battalion logistics with autonomous systems. This transition will significantly reduce maintenance requirements and PMCS man-hours while greatly enhancing point-to-point logistics and delivery at the point of need.

This shift is not simply a technological upgrade; it is a transformation of the logistics warfighting function itself. Every manned vehicle removed reduces fuel consumption, signature exposure, maintenance burden, and personnel risk. The T/E optimization is not about doing less with less—it is about doing more, smarter. It aligns with MCDP 4: Logistics and Installations and Logistics 2030, both of which advocate for autonomous, survivable, and dispersed sustainment solutions tailored to the character of 21st-century warfare.

Tactical Aerial Resupply and Signature Reduction

Leveraging TRUAS TRV-150c drones (Group 2) and larger platforms for resupply isn't just about technological advancement; it's a strategic imperative for safeguarding Marine lives in increasingly complex and contested environments. TRUAS can replace multiple traditional 2½-ton resupply convoys in a single mission, delivering critical supplies to forward operating bases and dispersed units that would otherwise require a complex and risky ground movement. By replacing these vulnerable convoys with rapid, distributed aerial resupply, we drastically reduce the exposure of our personnel to IEDs, ambushes, First Person View (FPV) drones, and enemy fire. It's about taking Marines off dangerous roads, minimizing their signature, and delivering critical supplies precisely where and when they're needed, ultimately, ensuring they have the resources to succeed and return home safely.

This shift towards drone-based logistics represents a human-on-the-loop approach to modern warfare, prioritizing the safety and survivability of our Marines. This system aims to reduce risk by minimizing unnecessary exposure when autonomous systems can easily replace human missions. It empowers commanders with enhanced agility and responsiveness, enabling rapid adaptation to evolving battlefield situations and ensuring critical supplies reach dispersed units with reduced threat to personnel. The Arcturus JUMP 20 Group 3 UAS, for example, can rapidly redeploy 30 lbs of medical supplies, fuel, or ammunition to a unit facing unexpected challenges, offering a level of responsiveness that traditional convoys simply can't match at a range of 185 km. Furthermore, the medevac capabilities of these TRV-150 and similar drones offer a lifeline to wounded personnel, potentially saving lives and reducing the long-term consequences of injuries. Investing in these technologies is an investment in our Marines, ensuring they have the best possible tools and support to accomplish their mission and come home. Every MTVR removed means one less exhaust plume, fewer thermal hotspots, and less radio traffic.

Logistics Decentralization and Support Unit Alignment

Decentralized logistics is critical to future force projection and directly supports the Marine Corps’ shift towards a more dispersed and agile battlefield as outlined in I&L 2030. Furthermore, it enables “push logistics capability forward, decentralize distribution, and eliminate static nodes.” Reducing manned platforms within the LAR battalion, coupled with the integration of organic autonomous systems, empowers smaller, more flexible units to conduct sustainment operations independently. This self-sufficiency reduces the burden on Combat Logistics Regiments (CLRs) and higher echelon logistics units, enabling them to focus on operational reach and strategic sustainment. This aligns with I&L 2030's emphasis on pushing logistics capability forward, decentralizing distribution, and eliminating vulnerable static nodes. Moreover, the convergence of Army SMET and Marine Corps UGV programs fosters cross-service interoperability, allowing for the rapid and scalable integration of logistics detachments within Joint Task Force (JTF) operations or Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) engagements, enhancing joint logistics and operational synergy. This distributed approach improves responsiveness, resilience, and survivability in contested environments.

Doctrinal Alignment: Contested Logistics and Force Design

The 2023 update to MCDP 4: Logistics affirms that, “Future battlefields will deny persistent resupply. Logistics must evolve from just-in-time to just-in-case, and rely on automation, deception, and dispersion.” Similarly, Installations and Logistics 2030 directs a shift from a “manned, wheeled-vehicle fleet” to “a mix of crewed and uncrewed, manned and unmanned logistics platforms across domains.” These reductions directly support that vision, freeing space and sustainment margin to field UGVs and aerial resupply assets. Force Design and the Commandant’s annual updates emphasize expeditionary autonomy, distributed operations, and reduced manpower reliance. “Lighter, lower-signature logistics formations are essential,” the 2023 report states, “not just to sustain distributed operations, but to survive them.”

Robotic Combat Vehicles: Lift and Lethality / Protection

While EMAV and MMSP plays a central role today in the Marine Corps’ emerging UGV inventory, we must also prepare to integrate and adapt the Army’s Robotic Combat Vehicle–Light (RCV-L) and Medium (RCV-M) programs, and newer technology to the Ground Combat Element (GCE) combat and logistic formations. The Army’s RCV-L is designed to “fight forward of manned formations, conduct route reconnaissance, and deliver direct fire support,” while the RCV-M is “heavily armed and capable of maneuvering alongside infantry or armored forces.” These vehicles, would enhance LAR now and the ARV formations tomorrow where survivability, mobility, and standoff are at a premium. Their integrated autonomy kits, turret options, and power architectures make them adaptable to light armored attack but also cargo, CASEVAC, or decoy roles, depending on the mission. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisition, Logistics and Technology) states: “Robotic Combat Vehicles provide a decisive advantage when used to reduce soldier exposure, extend operational reach, and enable force reduction without degrading combat effectiveness.” For the Marine Corps, particularly in force-optimized LAR and other heavy junk battalions, these advantages directly support reduced manning objectives and force structure savings.

Manned-Unmanned Teaming: Loyal Wingmen on the Ground

As the Army experiments with robotic Stryker support, the Marine Corps can adopt a similar Manned-Unmanned Teaming (MUM-T) approach to combat and logistics formations. This concept, long used in aviation, is evolving into ground formations where “loyal wingman” or Tactical Ground Sentinel / Loyal Rover UGVs accompany manned LAVs or JLTVs to carry fuel, ammunition, sensors, electronic decoys on the march or even into an attack. These vehicles serve as autonomous companions that watch, sense, and protect, offer robust mobility, ground-based sensing, in a reconnaissance capable platform. Tactical Ground Sentinel / Loyal Rover platforms can be pre-programmed to follow terrain, mirror formations, or rendezvous at preplanned grids. Future generations will be employed in the mothership concept in a two to one or three to one, where the manned vehicle is supported by several unmanned vehicles. By pairing unmanned RCV-Ls with reconnaissance or fires elements, the battalion can extend operational time without increasing crew load or risking additional Marines. This also addresses manpower pressures created by Force Design’s reshaping of maintenance and logistics billets—doing more with fewer Marines by augmenting with autonomy.

The integration of EMAVs, MMSP, and TRUAS into the battalion directly supports doctrinal resupply methods outlined in MCWP 4-11 and MCDP 4, including Tailgate, Service Station, and Combination Resupply methods. In a Tailgate Resupply scenario, EMAVs or RCV-L-class UGVs can autonomously deliver Class V, III, and IX directly to maneuver elements at pre-coordinated points, minimizing dismount time and exposure. For Service Station Resupply, TRUAS platforms such as the TRV-150C can rapidly emplace supplies along concealed or elevated routes, allowing units to rotate through resupply nodes without the signature or vulnerability of large vehicles. In environments requiring a hybrid approach, EMAVs can be positioned in terrain-masked zones while TRUAS performs final-leg aerial delivery to forward positions. Emergency resupply—historically the most dangerous—now benefits from TRUAS’s ability to insert critical items like blood, water, or munitions directly to point-of-contact units under fire. Additionally, pre-positioned caches can be staged via UGV in austere or inaccessible terrain during shaping operations, while TRUAS remains on alert for aerial sustainment or casualty evacuation. This layered, unmanned logistics architecture is not only doctrinally sound—it offers a scalable, survivable model for sustaining distributed forces inside the adversary’s weapons engagement zone.

Lethality Today and Tomorrow

The Loyal Rover UGV prototype offers a pathway to transform LAR operations today and tomorrow, serving as a force-multiplying companion to both the legacy Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) fleet and the forthcoming Advanced Reconnaissance Vehicle (ARV). In its intended “mothership” construct, a single manned LAV or ARV would control and sustain three semi-autonomous Loyal Rovers, combining the mobility, firepower, and command-and-control of manned platforms with the distributed sensing, persistent presence, and risk-tolerant employment of unmanned systems. This 3:1 ratio draws directly from U.S. Army Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV) experimentation, where manned platforms serve as battlefield coordinators and unmanned systems extend reach, accelerate targeting, and protect crews from unnecessary exposure. By integrating the Loyal Rover into current LAV formations, the Marine Corps could begin building manned–unmanned teaming proficiency now, ensuring a seamless transition when ARVs enter service in the late 2030s.

Loyal Rover’s modular design enables rapid reconfiguration for diverse mission profiles. In a reconnaissance screen, one UGV could carry a mast-mounted EO/IR sensor suite and ground surveillance radar for persistent observation, while another mounts precision direct-fire weapons, loitering munitions, and counter-UAS capabilities to engage threats before they threaten the manned force. A third could integrate electronic warfare and signals intelligence payloads to locate, disrupt, or deceive enemy command-and-control. These configurations are as applicable to a LAV company in today’s fight as they are to an ARV troop in the future, providing immediate utility without waiting for new platforms. The result is a layered reconnaissance force that can push sensors and fires forward while keeping manned vehicles in covered positions, consistent with the Marine Corps’ reconnaissance–counter-reconnaissance (RXR) imperative.

The employment cycle for Loyal Rover remains consistent across both fleets. Manned vehicles preload mission data and tasking before contact, then deploy the three Loyal Rovers in a dispersed formation to establish a forward and lateral security screen. As they advance, the UGVs feed fused sensor data to the mothership, enabling timely fire missions, route clearance, and enemy identification without exposing crews. In contact, the Loyal Rovers can fix enemy reconnaissance elements, deliver precision effects, or even conduct limited resupply using TRUAS-like payloads. The manned platform remains in overwatch, preserving combat power while directing the tempo of the engagement. This concept aligns with Army MUM-T practices but adapts them to LAR’s expeditionary mobility, distributed operations, and maritime integration requirements.

By fielding Loyal Rover with both LAV and ARV formations, the Marine Corps can close the gap between current capability and future potential. Early integration builds operator proficiency, informs doctrine, and refines the sustainment model for unmanned systems before ARV fielding. Once in the ARV era, Loyal Rover would be fully nested in a digital command architecture, leveraging enhanced bandwidth, on-the-move networking, and integrated kill chains. In both near-term and future fights, the mothership–companion construct offers a way to push reconnaissance assets farther forward, impose dilemmas on the enemy, and preserve the force for decisive action—ensuring that LAR remains relevant, survivable, and lethal in the decades ahead.

Vignette – Luzon Strait (2033)

A 3d LAR company, equipped with a mix of legacy LAV-25s and newly fielded ARV-30s, screens a joint force maneuvering through the northern Batanes Islands. Each troop deploys Loyal Rover UGVs in a 3:1 mothership construct, pushing them several kilometers ahead of manned vehicles. One Rover, configured for ISR, crests a ridgeline and silently observes a Type 15 light tank troop moving to establish a blocking position. Another Rover, armed with precision fire munitions, receives targeting data via mesh network and executes a coordinated strike, destroying the lead vehicle before it can occupy high ground. The third Rover, fitted with EW payloads, disrupts local drone control frequencies, blinding enemy reconnaissance. The manned ARVs remain under cover, orchestrating fires and maneuver while the LAVs, acting as mobile reserve, reposition to exploit the breach. The enemy never closes within line of sight of a Marine crew—proof that the mothership–companion model extends reach, preserves combat power, and delivers decisive effects in contested battle space.

Conclusion

As the Commandant aptly stated, “Logistics is no longer a back-office enabler—it is a front-line capability. If it fails, maneuver fails. If it survives, we win.” This isn't just a soundbite; it's a call to action for every Marine—especially those of us in the LAR community or heavy junk unit who understand that survivability hinges on the ability to sustain under fire. Imagine a squad pinned down, low on ammo, and miles from the nearest resupply point. In the past, that might have meant a dangerous and time-consuming mission for fellow Marines. But now, picture this: a small, unmanned vehicle, barely visible to the enemy, silently delivers the critical supplies they need, keeping them in the fight and potentially saving lives.

This transition is more than a technical upgrade—it is doctrinal alignment with MCDP 4, Installations and Logistics 2030, and Force Design, all which demand logistics formations that are lighter, faster, more autonomous, and survivable. By embracing these systems for logistics and combat operations, we lighten the physical and operational burden on our Marines, reduce their exposure to enemy fires and ISR, and expand the tempo, reach, and resilience of small units operating far forward. We move from a model of reactive, manned convoys to proactive, autonomous sustainment in depth.

The future of logistics in 3d LAR Battalion is already taking shape as the unit transitions from legacy 7-ton trucks and LVSRs to EMAVs, MMSPs, and TRUAS. To date, 3d LAR has certified 13 Marines in EMAV operations, is actively collaborating with the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL) on MMSP certification, and is preparing to qualify 0411s and motor transport operators in TRUAS and other autonomous vehicle platforms. This progress would not have been possible without MCWL and its partners. Their support, innovative thinking, and willingness to challenge conventional approaches have been instrumental—and continue to impress.

However, this progress has not come without resistance. The process has encountered unnecessary friction—I have been told “no,” questioned on “why,” and denied school seats with the justification of not “rating” or not being “in the fielding plan.” These mindsets and bureaucratic barriers hinder modernization. If the Marine Corps is serious about transforming sustainment for the future fight, units and sections must abandon parochialism, stop guarding their “rice bowls,” and think beyond their immediate interests. This shift offers the promise of a lighter, more agile, and fully autonomous logistics architecture capable of sustaining distributed operations with fewer Marines and reduced risk to personnel. The technology, training, and capability already exist—what is needed now is the institutional will to act decisively and field them at scale.

EMAVs, TRV-150Cs, RCV-L/M, and MUM-T have existed since 2019. This is about lethality, mobility, and survivability. The Marine Corps has experimented with EMAVs and MULEs since 2015, yet none of these autonomous systems have been fielded at scale outside controlled demonstrations. That is no longer acceptable. We are past the experimentation phase. It is time to cut the T/E, field these capabilities in quantity, and integrate them into the daily battle rhythm of the GCE. If it's fielded, the Marines will figure it out.

Lieutenant Colonel John Dick is the commanding officer of 3d Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. He can be reached at john.dick@usmc.mil.

Great article and LtCol Dick is spot on pursuing getting the equipment and concepts fielded where they can be tested, measured, and tuned. Since the USMC no longer has the Tank Battalions, the LAR Battalions are the premier unit in the USMC to do so. They have the top to bottom inherent understanding of Logistics, the Combined Arms Mentality, and the MAGFT outlook; this is why they are the best ground unit to be the tip of the spear for Autonomous Systems in Logistics. I disagree with quite a few aspects of the concepts and I think technological capabilites are being oversold beyond reality. That doesn't matter, and will be irrelevant if 3d LAR can get this approach fielded. I would say don't throw out your old boots before the new ones are broken in; don't compel LAR to divest MT assets before the new stuff is actually proven to work. This si too important.